I spent my 36th birthday on a trip to MassMOCA to visit Steve Locke’s exhibition the fire next time, described as “a meditation on uniquely American forms of violence directed at Black and queer people.” I first encountered Steve when I was eighteen years old, a freshman at Massachusetts College of Art (this was before they added Design to the name). He presented a series of Visual Language lectures to the entire freshman class. It was our first real introduction to the power of images - a power that by the end of our education at MassArt we would, god willing, be able to understand and wield for ourselves.

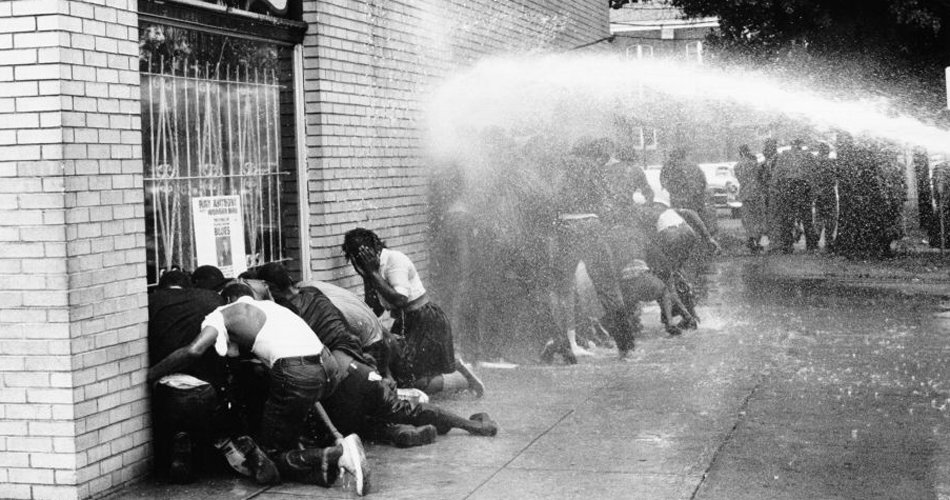

The singular indelible memory I have of those lectures was a black and white photograph he showed us. It depicted Civil Rights protestors in Birmingham, Alabama being sprayed with fire hoses.

(Frank Rockstroh / Michael Ochs Archives / Getty Images)

With the image enlarged on an enormous screen in the auditorium, Steve directed the entire freshman class: “Look at them. They are being sprayed with whiteness.”

I remember believing him at once, not understanding why, and hearing the skepticism of my classmates. “It’s just a snapshot. It’s just water. It’s just a black and white photo.” This was our first exposure to the power of an image - created by an artist, made up of choices: color, composition, light, value - to reflect our world and how we see it, whether we were ready to see it or not.

The next year, I declared Art Education as my major and signed up for every class with Steve that I possibly could. I did not know it at the time, but I had chosen to live out the original mission of MassArt. The college was founded to meet the need for trained art teachers after Massachusetts passed the Drawing Act of 1870, which required public schools to provide drawing instruction. This sense of purpose and urgency was instilled in us through Steve’s pedagogy. In his own words: “To study creativity and to live the creative life is to act on a practical set of skills forged in the studio and the library. This is not play. To live a creative life is to think and, most importantly, to act.”

My own career in education has brought me to many disparate settings - private schools in affluent towns, underfunded public schools in redlined neighborhoods, after school community organizations, and most recently, the museum - where I have carried out this mission. So on my birthday, eighteen years later, I could think of no better place to be than Steve’s show. It was a Monday, and the museum was so empty it felt like I had booked a private viewing. But inside the show, there was a bustle of activity and visitors. One of my favorite things to do in a museum is to watch how other people interact with the work.

A boisterous white woman with her family in tow approached the show. I heard some muffled laughter between her and the man with her as they looked at the names that make up A Partial List of Unarmed African-Americans who were Killed By Police or Who Died in Police Custody During My Sabbatical from Massachusetts College of Art and Design, 2014-2015. Pointing through the glass door into the exhibition, she brought her group’s attention to the harbinger, a large blue canvas with a floating head whose tongue is sticking out. She laughed loudly, “If Jeff were here he’d say some REALLY inappropriate things.” Some of her group asked if they should take pictures. She kept going: “It’s weird, I don’t like it. I am NOT going in there.”

Noticing me sitting on the bench across from her, her tone abruptly changed. Who knows what my face was saying (it speaks louder than me). She blithely trailed off “...but everyone can like different stuff,” and wandered away, leaving the older white couple with her lingering behind. Eventually they decided to go inside and see the show. I followed them because I love eavesdropping.

The old woman first noticed the graphite drawing of James Baldwin. “He was good. I still have The Fire Next Time, but the print is so small. It’s been so long it might crack if I try to open it.” She walked along the wall, following the trail of killers. Thirty painstakingly beautiful drawings of people like Dylann Roof, Carolyn Bryant, Derek Chauvin, each floating on a large white sheet of paper, encased in white frames underneath glass which reflects your own image. A few minutes later she told her companion: “It might be time to read Baldwin again.”

Curator Evan Garza, at a talk for an audience of MassArt alumni, faculty, and current students, told us of a recent tour they led through the exhibition. A white woman visitor complained that it would be easier for her if they had just put the label next to the drawing with the name of the person and the name of the person they killed. Garza told her, ‘if the artist were here, he would say to you, to your face, ‘I can’t make this easier for you.’” There is an implicit call in the work and its presentation for you to do your homework, to fully feel your discomfort and transform that into action - learning more, doing more.

The classroom has long been the frontline of the culture war. As the onslaught of attacks on education rain down on us from the Trump administration; as public schools are dismantled to give way to privatized systems; as students are terrorized by the possibility of ICE agents abducting them from their schools; as queer teachers and students are forced back into the closet; as “patriotic education” threatens to bury the truth of our history, we must find alternative places where we can educate.

The museum can be that place. The gallery can be that place. Our communities can be that place. As the artist and educator Luis Camnitzer said, “the Museum is a school; the Artist learns to communicate; the Public learns to make connections.” In spaces where creation and connection are emphasized we have an opportunity to participate in the slow, engaged looking that opens our thinking to new and often contrary perspectives. Liking a work of art is not a prerequisite to learning from it. Many enter a museum and look at a work demanding “impress me.” The teacher can persuade the viewer to approach a work with curiosity and in doing so resist the kneejerk thinking that is pervasive in our country. In our precarious democracy, this kind of art education is integral to truth telling, to finding our common humanity, to steeling ourselves for this work that cannot be made easier.